ARTS AND CRAFTS (RE)FORMS: Reform and Aesthetic Dress

Arts and Crafts artists focused on creating objects intended for domestic use and on living with these objects at home. This emphasis on the home, as well as on social reform and a new appreciation for handmade objects, was certainly within the domain of women. Thus there were opportunities for women that were hard to find elsewhere. Women were the first to organize Arts and Crafts societies, working at or for nearly every major Arts and Crafts business, organization or community beyond those restricted to men only.18 But, while a focus on the domestic sphere was accepted, increasing numbers of single women also sought more active lives outside of the home, attending college and entering professions and businesses.

A call for Reform dress had begun in the mid 19th century, as men and women argued that the amount of women’s underclothing, the constrictive corset, and the sheer weight of women’s clothes were all harmful to women’s health. These health reformers sought alternatives to the constricting and uncomfortable fashionable styles in attempts to make fashion rational, hygienic and beautiful. Like those reformers concerned with health, the aesthetic dress movement that began in England was concerned about the excessive weight of women’s clothing. However, they also objected to the ornamentation of Victorian dress, favoring a simpler and cleaner line and decoration. Aesthetic or artistic dress was sparked by influential artists and designers such as those of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a counterculture of artists and writers who viewed the rigid fashions of the day as artificial and unattractive. These painters, including John Everett Mallais (1829-1896) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) painted women in clothing inspired by classical, Medieval and Renaissance styles. These paintings increased the popularity of the style, at first within the art community, and then more widely.

"The question of what to wear can be answered by the analysis of what constitutes art and utility with beauty."25

– Annie Jenness Miller

Reformers in the U.S. were influenced by the aesthetic movement in Britain. Annie Jenness Miller (1859-) was one important advocate for dress reform or "correct dress." Through her publication Dress, The Jenness Miller Magazine, she stressed "adaptation of art principles to life and to dress," and her magazine often featured what she labeled as artistic dress.45 Similar to Arts and Crafts tenants of "truth to nature" and "utility," Jenness Miller stressed the "divine beauty and purity of the [natural] human figure,"25 and argued that true ideal beauty could be achieved by returning "the body to its natural form"25.

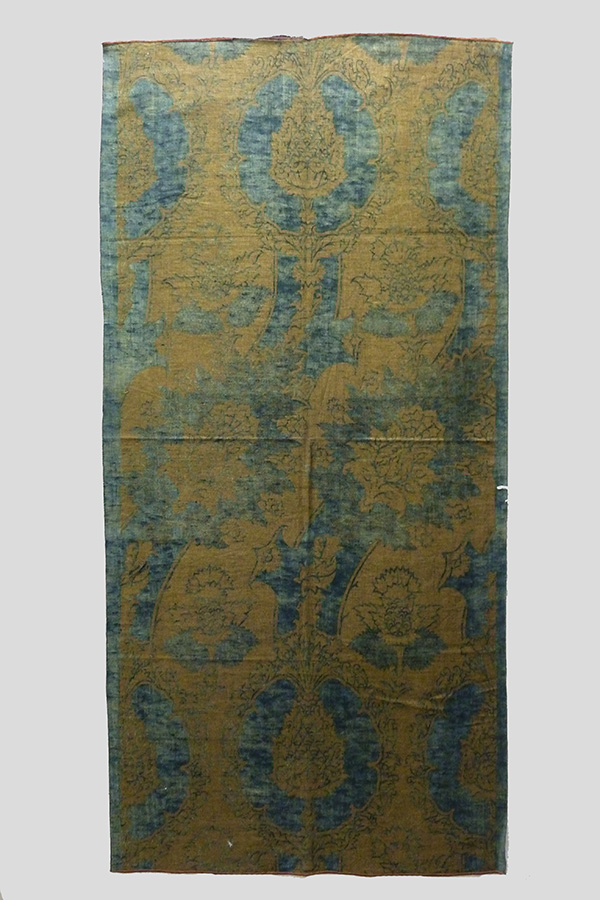

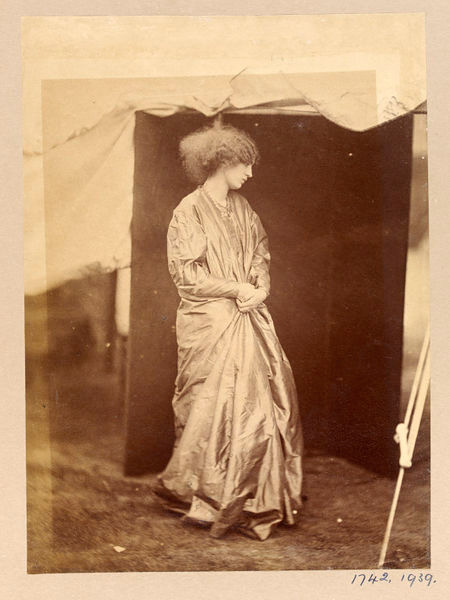

Rejecting the restrictive, tailored clothing of the Victorian era, Aesthetes and practitioners of Artistic and reform dress embraced less-ornamented, softer, more comfortable clothing inspired by historic examples. Loose, un-corseted styles were reminiscent of those worn in ancient Greece and medieval Europe, with surface design often influenced by the Far East. The most popular forms of artistic dress reflected a high-waist Empire style which became the dominant silhouette between 1909 and 1915, although it had emerged earlier in the form of the tea gown. The tea gown, or looser house gown was initially worn only in the home while entertaining close friends. A fashionable garment during the 1880s and 1890s, the tea gown was viewed by many as a rational garment, as women could choose to wear it without a corset.25

In 1890, a group within the Arts and Crafts movement formed the Healthy and Artistic Dress Union to promote dress reform. Walter Crane illustrated fashions in the Union’s journal, Aglaia, styles that shared design elements with those of classical Greece, and the Empire and Renaissance periods. Examples of articles championing dress reform include Types of Artistic Dress, How to Dress Without the Corset, and The Progress of Taste in Dress. The Healthy and Artistic Dress Union was supported by internationally successful textile designer and importer Arthur Lasenby Liberty (1843-1917) of Liberty & Company of London who made artistic styles of dress readily available in his well-publicized catalogs and shops throughout Europe and New York. His artistic styles of dress were frequently favored by Arts and Crafts proponents, as well as followers of artistic and aesthetic dress. Some of the most celebrated avant-garde fashion designers of the early twentieth century such as Paul Poiret (1879-1944) and Mariano Fortuny (1871-1946) were also well acquainted with the period’s modern styles, offering garments similar to other artistic dress forms with historic and Eastern influences.

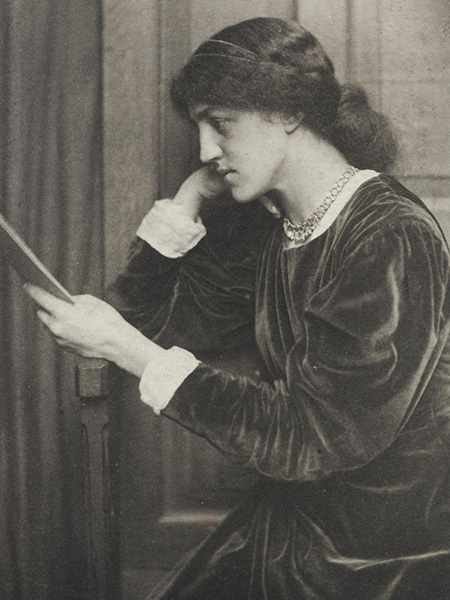

Arts and Crafts embroidery artist Jessie Newbery’s textiles training and politics found a "perfect outlet in the artistic dress movement."28 Between 1903 and 1909, Newbery’s artistic dress designs were produced in the German publication Das Eigenkleid der Frau by Anna Muthesius, a three-volume series regarded as a seminal text in the development of early twentieth century dress and is particularly associated with the Artistic movement’s costume, design and fashion. Jane Morris, wife of Arts and Crafts figurehead William Morris, and his daughter Mary, often wore silhouettes referencing historical fashions and hinting at fewer restrictive undergarments. According to the William Morris Gallery, aesthetic dress became a defining look for Jane and others in the fashionable artistic sets who favored "rich, jewel-like colors such as ruby red, peacock blue, emerald green, and amber yellow; the material of their skirts was left to drape naturally, rather than be supported by a scaffold of crinolines; and they discarded corsets…."47. "Jane and the other women of the Aesthetic Movement established a new style of dress that made the unconventional fashionable and paved the way for women’s bodies finally being released from restrictive clothing"47.

Elbert Hubbard, founder of the influential Arts and Crafts community Roycroft, advertised serviceable styles of women’s garments in Roycroft magazines. Influenced by his wife, noted suffragist Alice Moore Hubbard, Hubbard devoted himself to the "cause of Woman." Alice Hubbard, along with her duties as general superintendent of Roycroft Shops and manager of Roycroft Inn, utilized the campus to promote socio-political reform.30 Her writings espoused defense of woman’s right to be considered equal to men. The Roycroft community became a site for meetings and conventions of suffragists, reformers, radicals, and freethinkers.29

The principles of reform dress were disseminated not only in books, periodical literature and by artists and designers, but also by one of the most culturally avant-garde tastemakers of the nineteenth century – playwright and critic Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) who travelled America beginning in 1882 with the production of his comic operetta Patience. Wilde lectured on numerous art subjects as well as dress reform. In Reforming Women’s Fashion 1850-1920: Politics, Health, Art, Patricia Cunningham states, "In one lecture regarding women’s clothing titled ‘Slaves of Fashion,’ Wilde deplored the evils of corsetry. In another, ‘Women’s Dress,’ he advised women to make their dress hygienic by suspending the weight of the clothing from the shoulders and reducing the number of layers of clothing"25. He argued that beautiful and healthy garments could be created by looking to historic fashions and classical and Japanese art. Three years later in 1885 Wilde wrote The Philosophy of Dress in which he argued that dress was made "for the service of humanity. I care a great deal for the wonder and grace of the human form, and I hold that the very first canon of art is that Beauty is always organic and that it comes from within, from the perfection of its own being and not from any added prettiness… and that consequently the beauty of dress depends entirely and absolutely on the loveliness it shields, and on the freedom and motion that it does not impede."26

The components of reform and Aesthetic dress – purity of the natural human figure; the use of less ornamented styles of dress to achieve ‘true, ideal beauty;’ and the influences of historical and Eastern elements – are but a few similarities linking reform dress to the Arts and Crafts movement. Just as the foundation of Arts and Crafts was to craft beautiful decorative objects that remained true to the domestic purposes for which they were intended, so, too, did the foundation of reform and Aesthetic dress remain true to the purpose for which it was designed: decorate the human form to reveal it’s natural beauty while enabling its movement.

18 Zipf, Catherine W. The American Arts and Crafts Movement and its Women Practitioners. http://journalofantiques.com/features/wrought-by-her-hands/

25 Cunningham, Patricia. Reforming Women’s Fashion 1850-1920: Politics, Health and Art. Kent: Kent State University Press. 2003.

26 Wilde, Oscar. Philosophy of Dress. 1885. http://bigbang.uniroma1.it/images/stories/perazzini/The%20Philosophy%20of%20Dress.pdf

28 Das Eigenkleide Der Frau and Artistic Dress. Glasgow School of Art Libraries. https://gsalibrarytreasures.wordpress.com/2014/12/18/das-eigenkleid-der-frau/. Retrieved May 2019.

29 https://www.crookedlakereview.com/books/saints_sinners/martin15.html Retrieved April 2019.

30Hoyle, John T. In memoriam: Elbert and Alice Hubbard. East Aurora, N.Y.: The Roycrofters, 1915. https://archive.org/stream/inmemoriumhub00hoylrich#page/46/mode/2up