Endangered – Fauna and Fashion: Feathers

By Nicole Johnston and Jean Parsons

September 20, 2018

Feather ornamentation may have been worn in prehistory by Neanderthals. In a prehistoric cave site near Verona, Italy, over 660 bird bones were discovered with marks indicating the intentional removal of large feathers believed to be used as body decoration. Evidence of plumage adornment has also been found in indigenous Peruvian, Mesoamerican and Native American archaeological sites prior to European contact in the 15th and 16th centuries. In the 17th century, plumassiers (feather workers) crafted ostrich, peacock and heron feathers into a variety of accessories. By the late 1800s fashionable women of the West began wearing hats adorned with feathers, wings and even whole birds or their disembodied parts. In the 20th century, designers such as Yves Saint Laurent and Cristobal Balenciaga utilized feathers as replacements for fur on coats and dresses.

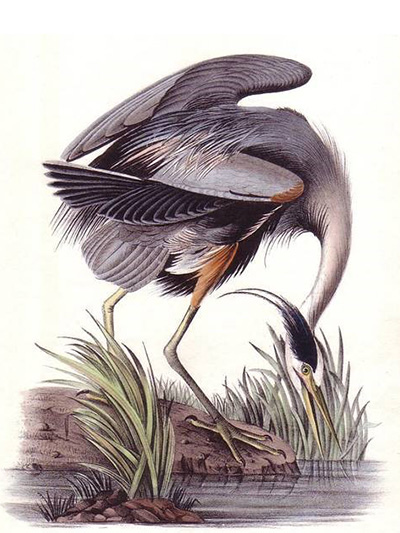

Continue below to view feathered artifacts from University of Missouri collections. Click on the image to the right to learn more about the formation of Audubon and conservation societies in the U.S. and to view lithographs from the State Historical Society of Missouri’s octavo edition of John James Audubon’s The Birds of America (1840-1844.)

John James Audubon

John James Audubon

North American Bird Lithographs State Historical Society of Missouri

MHCTC Felted Wool Hat with Egret Feather Accents (1930s)

MHCTC Felted Wool Hat with Egret Feather Accents (1930s)

Ornamentation on women’s hat became increasingly exotic in the last quarter of the 19th century, and the feather trade expanded its enterprise to include marketing some 64 species of native birds. Herons, with their extravagant breeding plumage – the Great Egret and the Snowy Egret – suffered great losses as the sources of supply began to disappear. One auction record alone recorded more than one million heron or egret skins sold in London between 1897 and 1911.1 Packages of heron plumes that averaged 30 ounces were sold. It required about four birds to make an ounce of plumes.2During the height of the feather trade (1870-1920),tens of millions of birds were killed, driven mainly by millinery centers in New York and London. In 1886 an estimated fifty North American bird species were being hunted and exploited for their feathers.3 The demise of the Carolina parakeet is one example. The only parrot native to the North American continent, the Carolina parakeet’s extinction came shortly after its beautiful, colorful feathers became fashionable to wear as decorations on ladies’ hats. The last known wild specimen was killed in Okeechobee County, Florida in 1904, and the species was officially declared extinct in 1939.

MHCTC Lesser Bird of Paradise Skin used as Hat Ornament (1910s)

MHCTC Lesser Bird of Paradise Skin used as Hat Ornament (1910s)

Exploitation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries led to formation of the first Audubon and conservation societies in the early 1900s. Preservationists struggled to enact laws to prevent the killing, possession, sale, and importation of plume birds and ornamental feathers. Enactment of federal laws began with the Lacey Bird and Game Act in 1900 which prohibited interstate commerce of protected species. But the law, poorly enforced, did little to slow the commerce in feathers. The National Audubon Society formed in 1905 and later assisted the passage of the Weeks-McLean Law by Congress on March 4, 1913, effectively ending the plume trade. The law, a landmark in American conservation history, outlawed market hunting and forbade interstate transport of birds. In 1918 the Migratory Bird Treaty Act banned feather imports and stopped the wholesale slaughter of migratory birds for ornamental feathers. With international protections in place, once-imperiled species began to rebound, including snowy egrets. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act established an important precedent for the Endangered Species Act of the 1960s and 70s that banned the transport of state protected wildlife. Today, feathers remain accents on hats, gloves, clothing and handbags. They are also widely used for various types of fishing lures. Many birds are raised domestically. Feathers are either plucked from the birds, or taken after the bird is killed for its skin or meat. In a bid for more humane methods, some farmers are collecting and selling only molted (shed) feathers.

- “The Feather Trade and the American Conservation Movement.” National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institute. Accessed June 16, 2018. http://americanhistory.si.edu/feather/fthc.htm

- Ehrlich, Paul R., D.S. Dokbin, and D. Wheye. Plume Trade. 1988. Stanford University. Accessed June 19, 2018. https://web.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/Plume_Trade.html

- Souder, William. “How Two Women Ended the Deadly Feather Trade.” Smithsonian Magazine. March 2013 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-two-women-ended-the-deadly-feather-trade-23187277/

- Costa, James T. On the Organic Law of Change: A Facsimile Edition and Annotated Transcription of Alfred Russel Wallace’s Species Notebook of 1855-1859. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2013. pg. 173.

- Kirsch, Stuart. “History and the Birds of Paradise: Surprising Connection from New Guinea.” Expedition, Vol 48, Issue 1. Accessed July 19, 2018. https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/history-and-the-birds-of-paradise/

Plume of Feathers, String and Leaves, Peru (1000 CE) Museum of Art and Archaeology

Bird of Paradise Hat Accessory (1900s-10s)

Silk Crepe and Marabou Feather Muff (1900s)

Marabou Feather Boa (1926)

Felted Wool Hat with Feather Accent (1930s)

Felted Wool Hat with Ostrich Feather Plume (1930s)

Felted Wool Hat with Feather and Net Accents (1930s)

Velvet Hat with Feather and Net Accents (1930s)

Felted Wool Hat with Ostrich Plumes (1940s)

Felted Wool Hat with Cock Feather and Net Accents (1940s)

Pheasant Feather Hat (1950s)

Felted Wool Hat with Egret Feathers and Rhinestone Accent (1950s)

Bark Cloth Breastplate with Parrot Wings, Toucan Head and Seeds, Jivaro, Ecuador (Mid 20th Century) Museum of Anthropology

Feather Hat by Christian Dior (1960s)

Polyester Gown with Marabou Feather Trim (1960s)

Feathered Wood Crown, Karaja, Brazil (1969) Museum of Anthropology

Egret and Arra Feathered Ficus Crown, Montaña, Colombia/Ecuador (20th Century) Museum of Anthropology

Feather Jacket (1990s)